Nile Magazine

Betsy Kissam with photography by Chester Higgins

Ethiopians speak of “children of the river” — yewenz lejoch in Amharic, the country’s official language. This phrase characterises people living near and relying on the water of a river for travel and nourishment, whether for their own needs or for the crops and livestock they depend on. The Blue Nile, Ethiopia’s most celebrated river, rises in the northern highlands and then journeys down into the deserts of Sudan and Egypt to the Mediterranean Sea. The depth and originality of the cultural legacy threading through the ancient cultures that flourished along this river challenges the imagination and awaits comprehensive analysis.

Roughly 200 years have passed since the study of the ancient Egyptian civilization began as a discipline. More recently, Egyptologists and archaeologists, in conjunction with efforts in Egypt, are concentrating on what’s buried beneath the sands of Nubia (in Egypt and Sudan) and Kush (Sudan). And in Ethiopia, archaeology is expanding under East African archaeologists and others from abroad.

Today, most Egyptologists recognize Egyptian culture as an African invention. In his 2010 book, The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt, Toby Wilkinson writes “The origins and early development of civilization in Egypt can be traced back to at least two thousand years before the pyramids, to the country’s remote prehistoric past.”

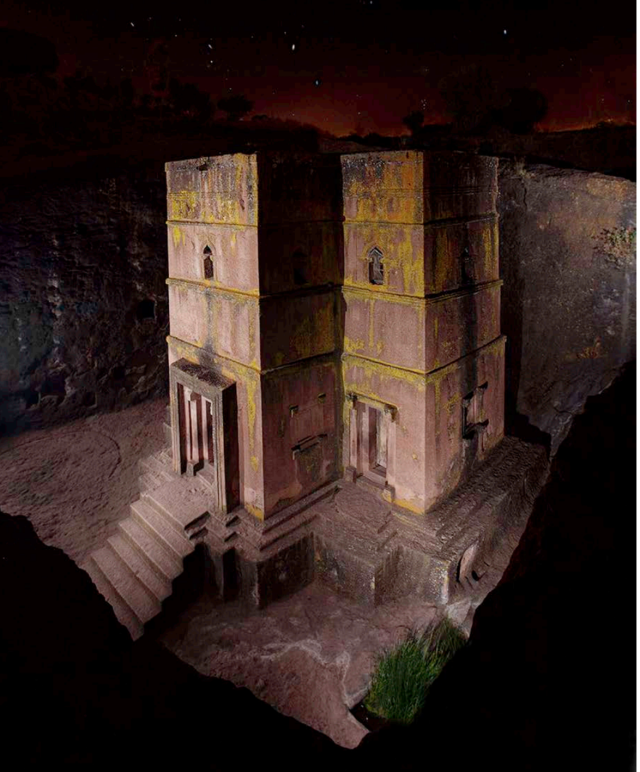

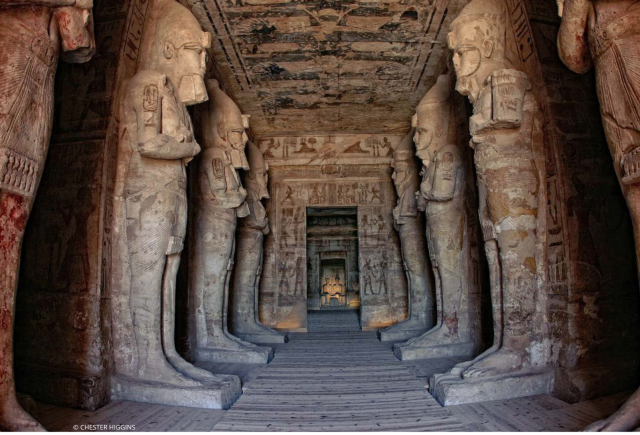

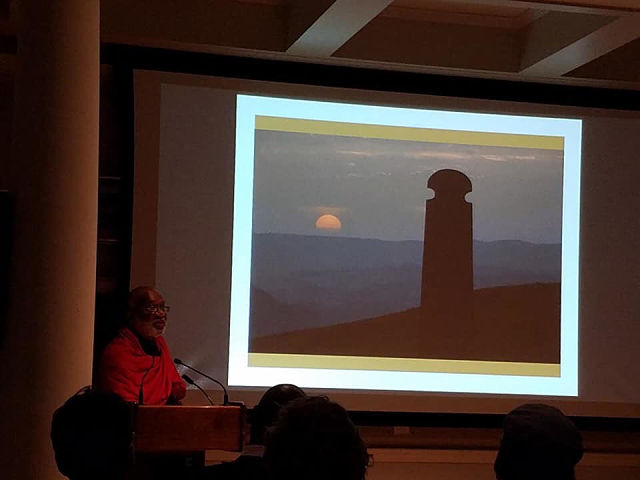

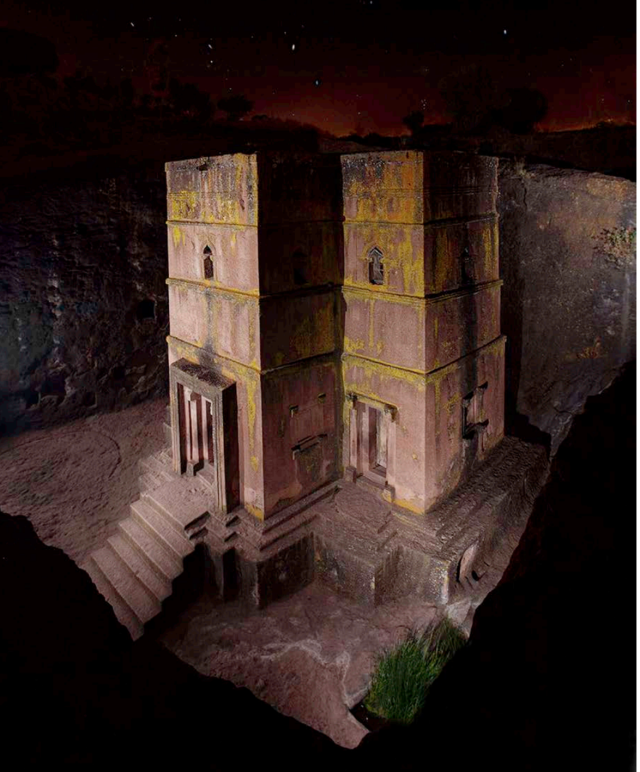

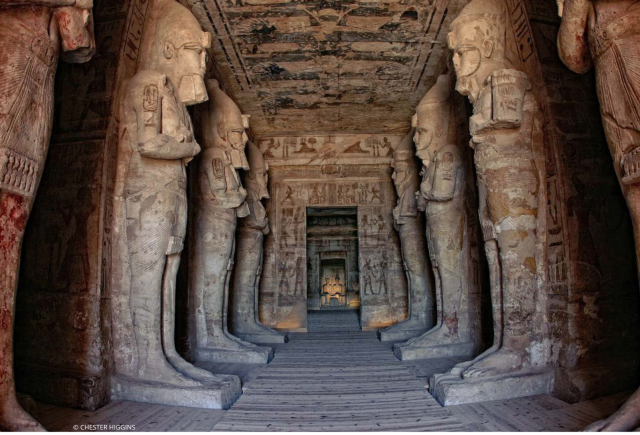

New York photographer Chester Higgins sees the Nile as a cultural thread; for the past four decades, he has been visually documenting Blue Nile cultures and seeking connections between the ancient people who made up the empires of Aksum (modern Ethiopia), Kush (Sudan) and Kemet (Egypt). Along this river, ancient excavators crafted sacred stone houses of worship out of solid mountains by chiseling away rock—rather than erecting a structure block by block.

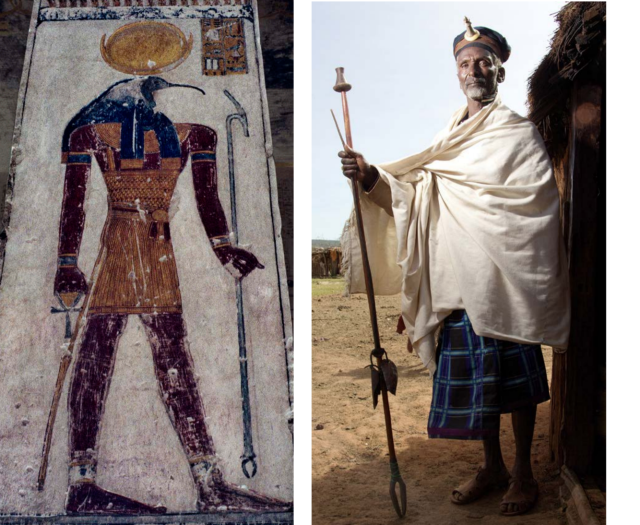

At the source and mouth of the Nile River are found the only monumental stone monoliths in Africa—phara-

onic and Aksumite obelisks. Images on Egyptian and Nubian tomb and temple walls bring to life symbols and the accouterments of early spiritual practice; when photographs of these are juxtaposed with those of rituals enacted in Ethiopia today, they focus links between “children of the river” in Egypt and Sudan—and farther south in the highlands of Ethiopia, the source of the Blue Nile.

Similarities in Higgins’s photographs, illustrate cultural connections up and down the river.

Much of the belief expressed today in our Abrahamic religions is rife with comparisons predicated on shared iconography and philosophy introduced millennia ago by people who honed their faith along the Nile River.

Ancient people left messages in stone, and skilled stone masons created precise structures from rock in situ along the Nile River. This is the exterior of the monolithic stone Church of St. George, in Lalibela, Ethiopia. The church was painstakingly fashioned out of solid volcanic rock in a cruciform structure, approximately 12 metres high, and standing in a 25 x 25 metre wide pit. The town of Lalibela is around 640 km north of Ethiopia’s capital, Addis Ababa, and today cares for 11 monolithic, rock-cut churches, which were erected in and around the year 1200. The buildings today are a living place of worship; they are home to a community of priests and monks, as well as being a place of pilgrimage for members of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church. (© Chester Higgins)

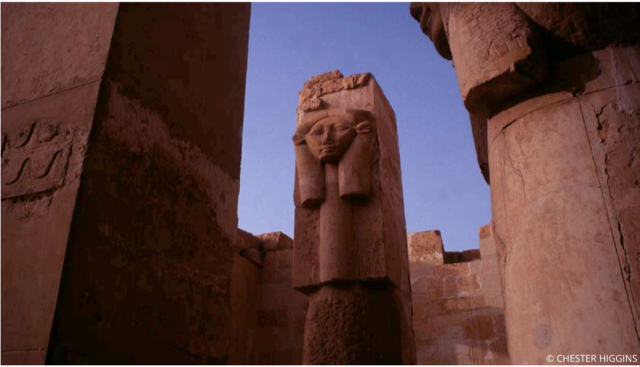

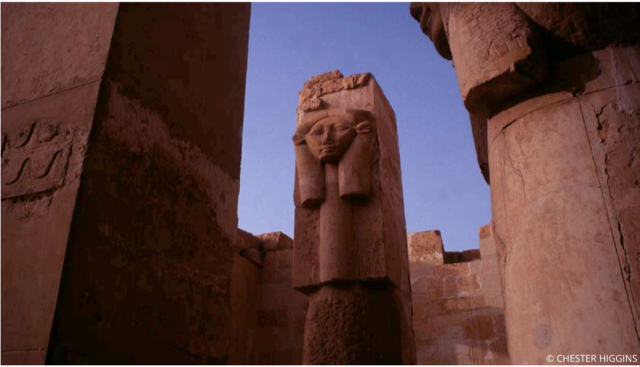

The monumental stone Temple of Ramesses II at Abu Simbel [in the Egyptian part of Nubia] has been dropping jaws since it was first hewn from a Kushite mountain some 3,300 years ago. Stepping into the temple’s Great Hall, the visitor is met by eight statue-pillars of Ramesses II portrayed as Osiris, god of resurrection. At the very back, the temple’s Sanctuary, which is illuminated by the rejuvenating rays of the rising sun twice a year. (© Chester Higgins)

There is something mystical, even supernatural, about the Blue Nile. When Herodotus identified Egypt as “the gift of the Nile” in the 5th century b.c., he had no knowledge of the source of the Blue Nile in the highlands of contemporary Ethiopia — 6,000 feet above sea level. But anyone who has witnessed the watery turmoil created by the Ethiopian summer rains can appreciate the otherworldly beauty of the frothing reddish volcanic soil in this water and its menace as it hurtles down mountainsides, tracking through ancient gullies and joining to form swift flowing streams, tributaries and then the impressive Blue Nile River.

The might of this river slices gorges through volcanic rock, creating sheer canyon walls, some more than 4,000 feet deep. Twisting and turning, juxtaposing broad sweeps with tight curves, the water turns north and drops down into the deserts of Sudan and Egypt. By the time the river reaches the desert at Khartoum in Sudan, where it commingles with the White Nile to form the Nile River, its elevation is 1250 feet having fallen nearly 5,000 feet in 900 miles. By the time the Nile reaches the Giza pyramids, its elevation is barely 64 feet. Before modern dams interrupted the flow, the Blue Nile carried about 80% of the water and fertile silt that transformed Egypt’s parched desert plains: surely the “gift” that Herodotus recognized.

The Nile’s water rises at a time when other rivers are lessening. Unsuccessful at working out an explanation for this phenomenon, Herodotus wrote “I was particularly anxious to learn from [the Egyptian priests] why the Nile, at the commencement of the summer solstice, begins to rise, and continues to increase for a hundred days—and why, as soon as that number is past, it forthwith retires and contracts its stream. . . .”

In the 1st century b.c., 400 years after Herodotus, Diodorus recorded “the Ethiopians. . . say, that the Egyptians are a colony drawn out from them by Osiris; and that Egypt was. . . made land by the river Nile, which brought down slime and mud out of Ethiopia.”

The boundaries of Ethiopia today on the Horn of Africa are not the designation accepted by the ancients that referred vaguely to the home of black people living south of the Mediterranean Sea.

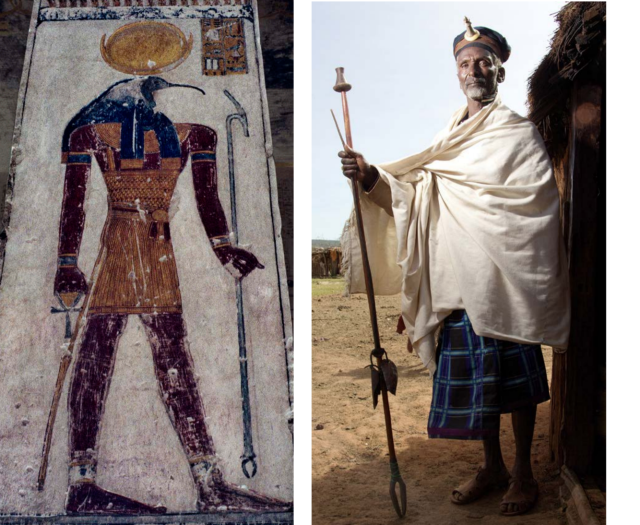

Left: The deity Thoth in the Tomb of Ramesses V (KV 9) that was later extended by his nephew Ramesses VI, in the Valley of the Kings [in Egypt]. Thoth holds a was sceptre (staff of authority), and sports a bull’s tail attached to the back of his kilt. Right: A Waka priest displays a staff of authority in Yebelo, Ethiopia. Contemporary Ethiopians, who honour the sacredness of nature, worship the sky deity Waka. The staffs of both the current Ethiopian example, and the ancient Egyptian version, end in distinctive curved forks. (© Chester Higgins)

The Blue Nile remained an ongoing siren song for the Greeks, Romans and other Europeans into the 15th, 16th, up to the 20th century — even after 16th and 17th-century Portuguese and Spanish Jesuits, accompanied by Ethiopian Emperors, visited and “discovered” the source of the Blue Nile, which they recorded in their travelogues published in Europe. In the 18th century, Scottish explorer James Bruce detailed his own version in his 1790 book, Travels to Discover the Source of the Nile.

Even with the source of the Blue Nile revealed and the Ethiopian rains recognized in Europe as the cause of its flooding, the river still guarded its mystery. For parts of its journey, narrow canyons protect the waters from everyone but the hardiest explorers, concealing much of the river’s exquisite beauty from all eyes except those of local highlanders, who themselves, it is said, rarely descend to the riverbed when it passes through gorges choked by volcanic rock, crocodiles and often malaria.

As late as 1925, the British Consul for Northwest Ethiopia, Major R. E. Cheesman, upon arriving in the country, was astounded to discover that “the latest maps showed the course of the Blue Nile as a series of dotted lines” — a substantial challenge for this 20th-century European as it had been for earlier travelers.

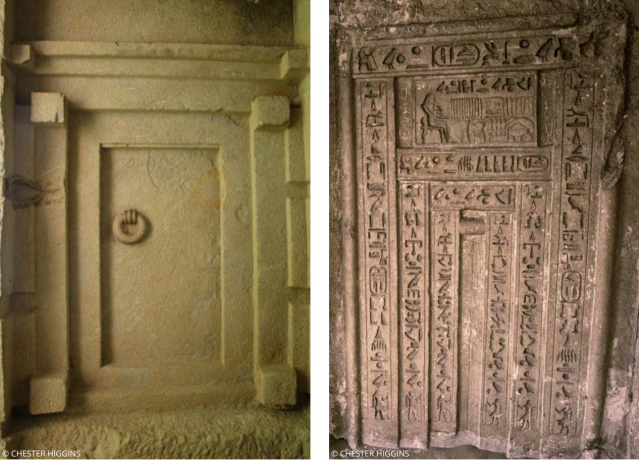

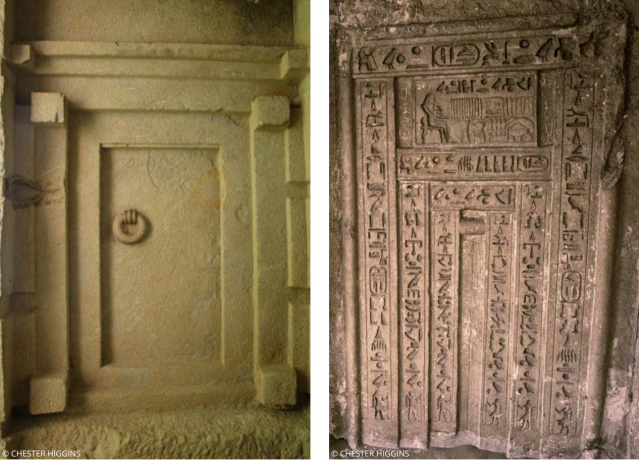

Stone obelisks are found along the Nile in Ethiopia and Egypt. In Aksum, Ethiopia, this 20-metre-high monolith stands tall in a field of such obelisks, which served as royal tomb markers. Aksum was a wealthy trading empire. At the Aksumite royal necropolis, false, or spirit doors were often placed at the base of the largest obelisks and above the entrances to tombs. This false door, featuring a finely carved ring pull door handle, was placed at the base (formerly southern face) of the now-fallen Obelisk #1—thought to have been the largest obelisk ever attempted to be erected: 32.6 meters long, and weighing 517 tons. (© Chester Higgins)

Obelisks in Egypt, erected in pairs in front of temples and topped with pyramidions, appear to function like billboards advertising a pharaoh’s accomplishments, and are dated by the pharaoh’s reign. Less well understood, Aksumite obelisks have been dated anywhere from around the 5th century b.c. to early a.d.; without inscriptions from rulers, the dates are open to conjecture. False doors in Egypt were placed outside tombs, within tomb chapels and in royal memorial temples, providing a focus for offerings to sustain the ka (divine essence) of the deceased. Like many elements of Egyptian funerary practice, they also served to emphasise the conspicuous wealth and social status of the tomb owner. This false door is in the tomb chapel of the mastaba of Khenu, near the top of the causeway of King Unas at Saqqara. Khenu was a 6th-Dynasty official who served the cult of Unas, the last ruler of the Old Kingdom’s 5th Dynasty (ca. 2375–2345 b.c.). © CHESTER HIGGINS

Many scholars believe that 18th Dynasty Egyptian Pharaoh Hatshepsut’s famous expedition to Punt, portrayed on her temple walls at Deir el-Bahari, situates Punt on the southern coast of the Red Sea

placing it in the proximity of contemporary Ethiopia. It is known the Egyptians built boats that were able to be deconstructed and reassembled in order to carry the boats around the Nile’s treacherous cataracts and sail the Red Sea. Other trade references to Punt were recorded by pharaohs as early as the 5th Egyptian dynasty.

A papyrus ferry on Lake Tana at the headwaters of the Blue Nile, in the Ethiopian highlands. This sort of craft seems to have barely changed since ancient times. (© Chester Higgins)

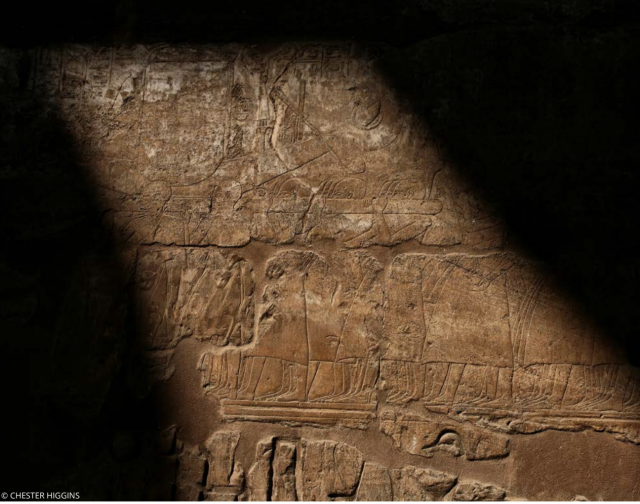

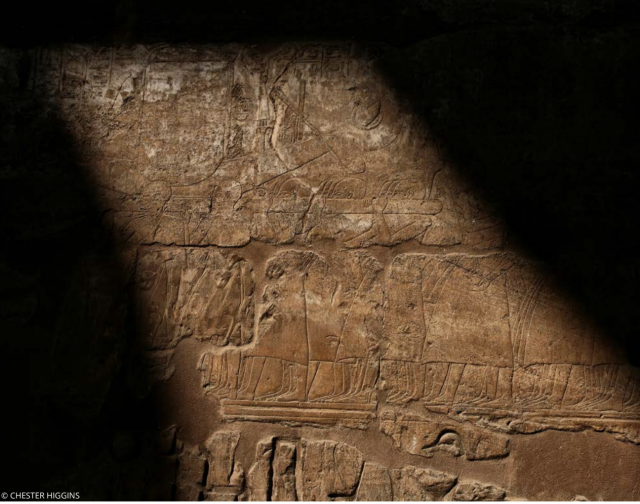

The pageantry of Timkat, the Ethiopian Epiphany Day—a celebration of the baptism of Jesus Christ—is celebrated by Orthodox Christians throughout Ethiopia. It echoes the joyous festival of Opet, recorded on Luxor Temple walls in Egypt, below. (© Chester Higgins)

Renewal is a strong theme for both rituals. Opet priests honor the Holy Family of Waset (Thebes/Luxor): they celebrate the union of the supreme deity Amen with his companion/wife Mut, and their son Khonsu, by bringing the sacred statues of the three deities from their shrines at Karnak Temple to visit the Temple of Luxor. Images on the wall of Luxor Temple show priests carrying the statues on their shoulders through crowded streets, and then by boat on the river. For Timkat, the high priests transport on their heads the churches’ sacred tabots (a replica of the Ark of the Covenant) through streets teeming with revelers, to join other tabots at a water source. (© Chester Higgins)

(© Chester Higgins)

(© Chester Higgins)

Left: Abu Haggag Mosque at Luxor Temple, Egypt. The mosque sits atop part of the ruins of Luxor Temple. It was built as a shine to a local saint, Sheikh Yusuf al-Haggag, who is credited for introducing Islam to Luxor. Sacred places often remain hallowed to successive faiths, and the mosque here stands on the site of an earlier Christian church. Right: An altarpiece from the Moon Temple at Yeha, Ethiopia. Around a.d. 330, Aksum’s Emperor Ezana made Aksum into one of the earliest Christian states, which saw the replacement of the Aksumite crescent and disk religious symbols with the Christian cross. On this site today, next to the Yeha Temple is an Ethiopian Orthodox Christian Church monastery. (© Chester Higgins)

Much later, in the 4th century a.d., Ethiopia became a Christian country after Aksumite King Ezana converted to Christianity. Bound by this faith, the Ethiopian Orthodox Christian Church entered into relations with the Coptic Church in Egypt, although these ties were often interrupted and conflicted. But the selection of Abunas, or Ethiopian Popes, came out of Egyptian monasteries until the 20th century when this link was severed by Emperor Haile Selassie.

Egyptologist Wallis Budge documented communication between Egyptian rulers and Ethiopian kings, foreshadowing the tension between the two countries today over down stream access to Nile water. In his 1928 book, A History of Ethiopia, Nubia and Abyssinia, Budge wrote about a seven-year famine in 11th-century Egypt: “it is said that the Khalifah Mustansir-b-Illah, thinking that the Abyssinians had turned the Nile out of its course, sent an embassy loaded with rich gifts to the king of Abyssinia, and asked him to let the Nile return to its old bed.”

A priest of the Ethiopian Orthodox Christian Church with two deacons at the Blue Nile Falls, near the city of Bahir Dar, Ethiopia. The “tails” on the vestments are an enigma, although they resemble the leopard pelts worn by the ancient Egyptian priests who presided over funerary rites, called sem priests. Depictions in Egyptian temples and tombs suggest that priests wore actual pelts, but nearly all of the rare surviving examples are made of painted linen. (© Chester Higgins)

Budge further recorded the words of an 18th century Ethiopian King, in the midst of a diplomatic disturbance, “the Nile would be sufficient to punish you, since God hath put into our power his fountain, his outlet, and his increase, and that we can dispose of the same to do you harm. . . .”

It seems there was interface among children of the river. But it is too early to know how much and whether this shared cultural legacy along the Nile dates back millennia or centuries, and if influence traveled upriver or down — or in both directions.

—

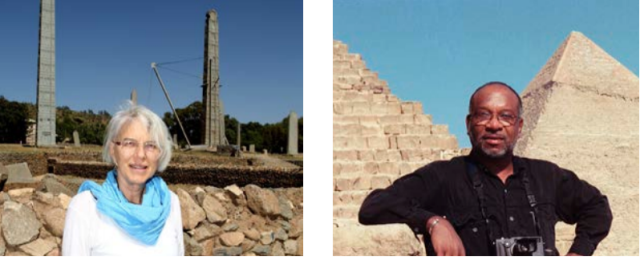

Left: BETSY KISSAM is a freelance writer and member of ARCE – NY. For the past four decades, she has been traveling with photographer Chester Higgins along the Blue Nile River in Ethiopia, Sudan and Egypt. Currently she is working with Higgins on a book project about the sacred passage of faith along the River Nile. Right: CHESTER HIGGINS is the author of eight books of his photography. Most recently he co-authored the book, Ancient Nubia: African Kingdoms on the Nile. For additional info see chesterhiggins.com and #chesterhiggins12.

Related:

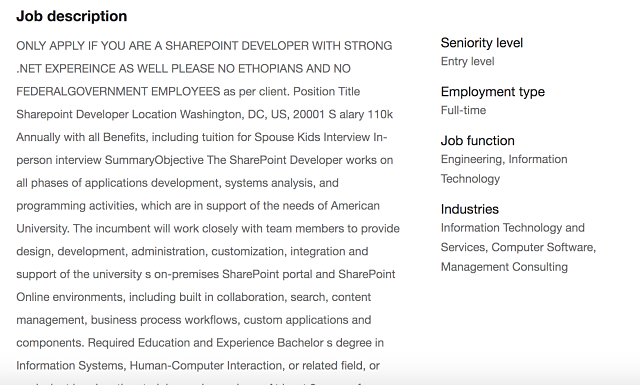

Photos: Chester Higgins Honored by Ethiopian School Readiness Initiative

Join the conversation on Twitter and Facebook.