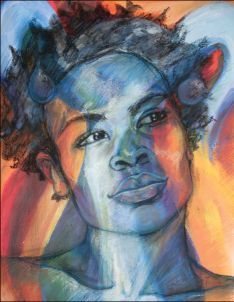

A Conversation with Dinaw Mengestu

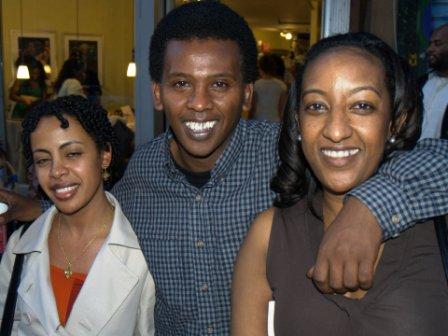

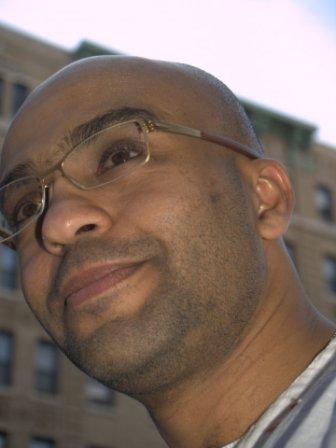

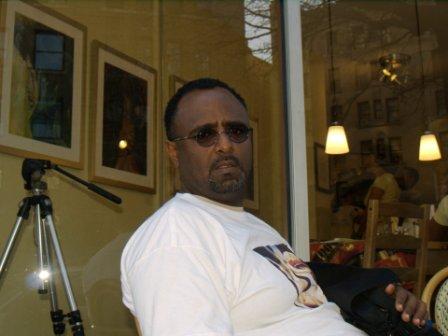

Dinaw Mengestu was born in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, in 1978. In 1980 he immigrated to the United States with his mother and sister, joining his father, who had fled the communist revolution in Ethiopia two years before. He is a graduate of Georgetown University and of Columbia University’s MFA program in fiction. A former intern at The New Yorker, he is the recipient of a 2006 fellowship in fiction from the New York Foundation for the Arts. He has also recently reported stories for Harper’s and Jane magazine, profiling a young woman who was kidnapped and forced to become a soldier in the brutal war in Uganda, and for Rolling Stone on the tragedy in Darfur.

The following is a conversation about The Beautiful Things that Heaven Bears, the debut novel of this immensely gifted young writer who eloquently evokes the experience not only of Ethiopian and African immigrants in general, but of African-Americans, and of all Americans whose identities are being redefined in a quickly evolving society.

How much of your own story and your family’s story is in this novel? How did you learn about your family’s experience?

The novel is definitely a blend of fact and fiction. The parts of the narrative that are true were told to me over the course of many years, sometimes by accident, sometimes deliberately. As is often the case with fiction, a certain factual detail becomes the starting point from which the rest of the narrative takes off. My uncle, for example, was a lawyer in Addis, and he was arrested and died during the government’s Red Terror campaign. The details of his death, however, are entirely unknown to me or anyone else in my family. Similarly, another uncle who was a teenager at the time did flee Ethiopia for Sudan during the Revolution, and while we’ve discussed his journey, it’s always in relatively vague and general terms, and that’s partly where the fiction element comes. It allows you to create the details that can bring a story to life.

Why do you think that the lives of African immigrants in the United States have been so little explored in fiction until now?

There have clearly been dozens of wonderful novels written by Africans about Africa. The African diaspora experience in America, however, is still in its early stages, especially with Ethiopia. My generation is the first to grow up in America, to know it well enough to write about it from “inside” the culture, so to speak, and I imagine as the years go on, there will be plenty of other similar narratives.

Although your book is written from the point of view of an African immigrant from Ethiopia, it is also in a sense an African-American novel, set in a primarily black neighborhood in Washington, D.C. Can immigrants from Africa offer a new perspective on race relations in the United States?

I wouldn’t say that this is an African novel, or African-American novel. To me, it’s a novel about America, with all of its competing and sometimes conflicting identities. Of course, growing up black and African in America has shaped my writing and experiences in more ways than I could possibly state, and yet I have to argue for the singularity of my opinion and perspective on this, which is to say I grew up and continue to live in different communities, some predominately white, some predominately African-American or African. Personally, for me, if there is a new perspective on race relations that comes from being an African immigrant it stems from this sense of never wholly identifying with one category.

More specifically, can you talk about some of the different ways that African-Americans and African immigrants experience American society? What is the relationship between the two communities like?

Obviously there is no simple or short answer to that question. If anything though, I would have to say it’s easy for people not to understand just how removed and disempowered many minority communities, particularly African immigrants and African-Americans feel from the country’s power structures, political, social, and economic. As for the relationship between the two communities, like any two closely intertwined communities there is a give and take, with ample room for misunderstanding and disappointment. In DC, for example, many within the African-Americans community were angered at a proposal to rename a part of the historically black U street corridor “Little Ethiopia.” That anger, of course, is entirely understandable, and in its simplest form, comes out the question, whose experience in America matters more?

Sepha Stephanos, your narrator and main character, has a very tentative romantic relationship with a white woman who moves in next door. Are the barriers to their relationship primarily personal, racial, economic, or some inextricable combination of all those?

In Sepha’s case, the barriers are very much a mix of all these factors, but perhaps most important to the novel is that mix of race and economics. I wanted to show how together the two can create vast, seemingly inseparable gulfs between people. Recently much more attention has been paid to the growing class and economic divide within America, and that divide, when coupled with race, magnifies the tensions even more.

The neighborhood in which you set your story is Logan Circle, which is rapidly being gentrified. More bluntly, prosperous white people are moving in and bringing economic pressures to bear on the poor black people who already live there. Can this sort of change ever go well?

Gentrification is one of those words in constant circulation these days, not only in DC but also in New York and I’m sure many other cities throughout the country. When it means mass displacement, the type of which is happening throughout DC and New York, where entire communities are being turned over, then no, I don’t think these changes ever really go well. At the same time, however, there has to be room for economic revitalization and rebuilding, the type that allows for a community to rebuild its own resources—schools, homes, businesses—while allowing for new growth.

Judith, the white woman in the novel, is a professor of American history, and one of her favorite quotation is from Tocqueville’s Democracy in America: “Among democratic nations new families are constantly springing up, others are constantly falling away, and all that remain change their condition; the woof of time is every instant broken and the track of generations effaced.” Does this quotation still describe the essential dynamic of American society, for immigrants and native-born citizens alike?

My interest with Tocqueville comes in large part from how accurate I think many of his observations about America still are. Tocqueville, while at times highly critical of America and its democratic spirit nonetheless respected the country’s inherent dynamic nature. Families, language, all of these are in a constant state of flux and evolution, which is a part of the great American myth—and I don’t use that term pejoratively—that each individual has the ability to change their circumstances, better their lives, and make themselves an entirely knew man or woman. Of course that ties in directly with one of the more common criticisms about America, which is its lack of regard for history.

Do you think there’s something new about the latest wave of American immigrants over the past few decades? Are their experiences in some ways fundamentally different from the experiences of the European immigrants of the early twentieth century, for example?

Obviously America’s ethnic make up is rapidly changing. The Hispanic community has become the largest minority community in the country, while at the same time there have been an ever-increasing number of African immigrants. Undoubtedly their experiences are going to be different, while at the same time, they will also be marked by some of the same burdens ranging from discrimination to low-paying jobs.

What do you think your novel has to say to all Americans, regardless of ethnic or racial background, about national identity?

I don’t know if novels are supposed to say anything. I think they exist to complicate and expand upon our understanding of the world and it is up to the reader to create their own personal meaning out of the narrative.

Is it ever possible for an immigrant to overcome the sense of being stuck between two worlds that Sepha feels? How is it done? What is the price that must be paid?

I’m sure many immigrants can and do overcome that sense, although I can’t say I personally know any. I was born in Ethiopia but I’ve grown up entirely in the United States and yet I’ve held on deliberately, at times fiercely, to a country that I hadn’t seen in twenty-five years. Many other immigrants I’m sure have a much stronger sense of the country they left behind and so perhaps for them it has less to do with being stuck between two worlds as it does with moving between two different realities. In Sepha’s case, Ethiopia has been physically left behind and he lives with that absence and refuses to let it go because nostalgia and memory are all he has.

Your title is taken from Dante’s Inferno. Can you recite that passage and explain how it is related to your story?

The passage comes from the last few lines of the Inferno, just as Dante is preparing to leave Hell. “Through a round aperture I saw appear, some of the beautiful things that Heaven bears, where we came forth and once more saw the stars.” I read the Commedia as an undergraduate, and then read parts of Robert Pinsky’s translation years ago. The last lines always stuck with me, as many wonderful lines in poetry often do. In this particular case it was the idea of beauty that struck me most. It’s an idea central to the novel, and it’s a word repeated throughout the narrative. Dante still has not made it to heaven yet, and won’t until passing through purgatory, and so there is an ambiguity to the language. The beautiful things are not named or described, and won’t be until Dante finally reaches heaven. And yet of course he can see a hint of what that beauty is. He knows it’s there even if he has not attained it. Joseph, one of the novel’s central characters, latches on to that idea of a visible but not yet attained heaven as a metaphor for his understanding of Africa.

Although your novel does not take place in a single day, Sepha goes on a crucial day-long journey through the streets of Washington that inevitably calls to mind Leopold Bloom’s journey in Ulysses. Was that a correspondence you were consciously seeking to evoke?

I wasn’t thinking of Ulysses explicitly while writing this novel, although of course I was aware of Bloom’s one-day journey through Dublin. The novel that probably proved the most influential in imagining Sepha’s trip through Washington DC was Saul Bellow’s Herzog. I’m sure even subconsciously the letters that Sepha reads were an echo of the letters that Herzog is constantly writing in his head as he wanders through New York and his own past.

Another work of literature that figures significantly in the novel is The Brothers Karamazov, which Sepha reads to Naomi, Judith’s bright young daughter. Are there thematic parallels between that work and your own?

The Brothers Karamazov was one of those novels that once read, never leave you, but I can’t say I chose it out of any obvious thematic parallels. I’m not even sure I would ever want to think of the novel in terms of thematic resonance. Alyosha’s speech that Sepha commits to memory at the end of the novel does tie in with a lesson that Sepha wants to pass onto Naomi, and of course himself, namely that we all seek some form of salvation from who we are and what we’ve become and that it’s possible to find that salvation in a memory of who we once were.

Sepha and his only friends, two fellow African immigrants named Ken and Joseph, regularly play a sarcastic game together. One of them names an obscure African dictator, and the others have to name his country and the date of the coup that put him power. Why are they so bitter and hopeless about their home continent?

I don’t actually think of them as being hopeless. Bitter, yes, but if anything it’s a bitterness born out of love. If they did not love and mourn for their home countries, and for the continent as a whole, they would never spend so much time mocking and eulogizing Africa. They are all realists, to one degree or another, and what they will not do is romanticize any of the continent’s failures, most notably those of its leaders.

You recently wrote a major piece about the crisis in Darfur for Rolling Stone, and you’re headed off now to Uganda on another assignment. What’s your own view about Africa’s future?

I still see more hope and potential in Africa than I do despair, and I say that after having seen it at its very worst. Part of why I went to Darfur and now northern Uganda is because like many Africans, I was tired of seeing the continent’s conflicts described as “hell,” or “hellish.” Yes, there is more misery and suffering than any one person should ever have to bear, but even in the case of Darfur, that is not the entire story. Underlying that misery and violence are remarkable people who continue to endure and survive despite their corrupt leaders.

When and how did you decide to become a writer?

I don’t think most writers ever decide to write. For me, it was something that I did because I had to. It’s been my way of managing and making sense of the world I live in.

Are you planning another novel yet? Can you describe what it’s about?

I am working on another novel, but it’s in such an early stage that I would hate to say what it will or will not become. I’m still figuring that out, which is part of the joy of writing.

—

Read here excerpt from The Beautiful Things That Heaven Bears