Figure 3: Hatse Bazin’s Stela at Aksum (Photo: Ayele Bekerie)

Tadias Magazine

By Ayele Bekerie

Published: Monday, March 15, 2010

Click here to read part one of this article.

Who are the authors of the external paradigm?

New York (Tadias)- Sergew (1972) represents the Ethiopian scholars who look at the Ethiopian history from outside in, one of the most ardent proponents of the external origin of Ethiopian history and civilization is Edward Ullendorff. In the preface to his book The Ethiopians: An Introduction to Country and People, Ullendorff (1960) wrote:

This book is principally concerned with historic Abyssinia and the cultural manifestations of its Semitized inhabitants – not with all the peoples and regions now within the political boundaries of the Ethiopian Empire.

The constituent elements of the external paradigm are thus “historic Abyssinia” and “Semitized inhabitants.” Regarding the name Abyssinia, Martin Bernal (1987), in his book Black Athena: The Afroasiatic Roots of Classical Civilization, Vol 1, wrote: “It should be made clear that the name ‘Abyssynia’ was used precisely to avoid ‘Ethiopia,’ with its indelible association with Blackness. The first American edition of Samuel Johnson’s translation of the 17th-century travels of Father Lobo in Ethiopia and his novel Rasselas, published in Philadelphia in 1768, was entitled The History of Rasselas, prince of Abissinia: An Asiatic Tale! Baron Cuvier equated Ethiopian with Negro, but categorized the Abyssinians – as Arabian colonies – as Caucasians.”

On the question of “Semitized inhabitants, Bernal (1987) appears to agree with Ullendorff. Bernal stated, “The dominant Ethiopian languages are Semitic.” I must add, however, Bernal now claims the origin of what is generally accepted as Afro-Asiatic or “Semitic” languages is Ethiopia. The possible diffusion of the Afro-Asiatic languages from Ethiopia to the Near East since Late Paleolithic times have also been emphasized by Grover Hudson (1977; 1978). This claim by itself is a major challenge to the South Arabian or external paradigm. Ullendorff’s claim that “the Semitized inhabitants of historic Ethiopia” had South Arabian origin has become difficult to sustain. It is, however, exemplary to look into the writings of Ullendorff in order to bring to light the process of linking the Ethiopian history to an external paradigm.

According to Ullendorff, “no student of Ethiopia can afford to neglect the connection between that country and South Arabia. Among those who have recognized this vital link are Eugen Mitwoch, while leo Reinsch is the undisputed master of the Semitic connection with the Hamitic (Kushitic) languages of Ethiopia.” Hamitic/Semitic divide, of course, was nothing but a means to keep the Ethiopian people divided.

His divisiveness even became clearer in the following statement: “The Abyssinians proper, the carriers of the historical civilization of Semitized Ethiopia, live in the central and northern highlands. From the mountain of Eritrea in the north to the Awash valley in the south we find this clearly distinguishable Abyssinian type who for many centuries has maintained his identity against the influx of Negroid peoples of the Nile Valley, the equatorial lakes, or the Indian Ocean littoral.” What is surprising is this outdated argument of physical anthropology that remained unchallenged until very recently. It is also unfortunate that a significant portion of the Ethiopian elite would buy such erroneous assertion.

The outline of Ethiopian history constructed by Ullendorff begins with “South Arabia and Aksum.” And the outline has been duplicated and replicated by a significant number of Ethiopian historians. For instance, Sergew used similar “external” approach in his otherwise very important book entitled Ancient and medieval Ethiopian History to 1270. Sergew (1972) wrote, “Ethiopia is separated from Southern Arabia by the Red Sea. As is well known, the inhabitants of South Arabia are of Semitic stock, which most probably came from Mesopotamia long before our era and settled in this region. … For demographic and economic reasons, the people of South Arabia started to migrate to Ethiopia. It is hard to fix the date of these migrations, but it can be said that the first immigration took place before 1000 B.C.11 Sergew essentially echoed the proposition advanced by Ethiopianits, such as E. Littmann (1913), D. Nielson (1927), J Doresse (1957), H.V. Wissman (1953), C. Conti Rossini (1928), M. Hoffner (1960), A. Caquot and J. Leclant (1955), A. Jamme (1962), and Ullendorff (1960).12 The Ethiopianists almost categorically laid down the external or South Arabian paradigmatical foundation for Ethiopian history.

Challenges of the External Paradigm from Without

In Aksum: An African Civilisation of Late Antiquity, Stuart Munro-Hay (1991) writes: “The precise nature of the contacts between the two areas [South Arabia and Ethiopia], their range in commercial, linguistic or cultural terms, and their chronology, is still a major question, and discussion of this fascinating problem continues.”13 What is notable in Munro-Hay’s interpretation is the very labeling of the Aksumite civilization as an African civilization. Its impact may be equivalent to Placid Temples’ Bantu Philosophy. At a time when Africans are labeled people without history and philosophy, the Belgian missionary in the Congo inadvertently overturned the Hegelian reduction of the so-called Bantu. Temples elevated the Bantu (African) by wanting to observe him in the context of reason and logic, that is, philosophy.

By the same token, Aksum: An African Civilisation dares to place or locate Aksum in Africa. That by itself is a clear shift of paradigm, from external to internal. It is an attempt to see Ethiopians as agents of their history. It is an attempt to question the validity of the south Arabian origin of the Ethiopian history and civilization.

Jacqueline Pirenne’s proposal has also convincingly challenged the validity of the external paradigm as the source of Ethiopian history. Pirenne suggests that the influence is in reverse, i.e., the Ethiopians influenced the civilization of the South Arabians. She reached her ‘ingenious’ conclusion after “weighing up the evidence from all sides, particularly aspects of material culture and linguistic/paleographic information.” Pirenne is essentially confirming the proposal made by scholars such as DuBois and Drusilla Dungee Houston, two African American vindicationist historians, who, in the early 1900s, wrote arguing that South Arabia was a part of ancient Ethiopia.

Another landmark in the refutation of the South Arabian paradigm comes from the Italian archaeologist, Rodolofo Fattovitch, who linked the pre-Aksumite culture to Nubia, “especially to Kerma influences, and later on to Meroe.” After more than three decades of extensive research and publications, Fattovitch in 1996 made the following conclusion: “The present evidence does not support the hypothesis of migration from Arabia to Africa in late prehistoric times. On the contrary, it suggests that Afro-Arabian cultures developed in both regions as a consequence of a strong and continuous interaction among the local populations.” Recent archaeological evidence from Asmara region also appeared to support the conclusion reached by Fattovitch. “Archaeologists from Asmara University and University of Florida, based on preliminary excavations in the vicinity of the Asmara, seemed to have found an agricultural settlement dated to be 3,000 years old.”

Challenges of the External Paradigm from Within

Among the Ethiopian scholars, Hailu Habtu (1987) presents a very strong case against the external paradigm. As far as Hailu is concerned, “the formulation of Ethiopian and other African historiography by European scholars at times suffers from Afro-phobia and Eurocentrism.” Hailu utilizes linguistic and historical linguistics evidence to challenge the external paradigm. Most importantly, Hailu suggested a new approach in the reading of the Ethiopian past by declaring the absence of “Semito/Hamitic dichotomy in Ethiopian tradition.” Hailu cites the works of Murtonen (1967) to question any significant linguistic connection between Ge’ez and the languages of South Arabia. According to Murtonen, “Ancient South Arabic is more closely related to northern Arabic and north-west Semitic rather than Ethiopic.” He also cites Ethiopian sources, such as Kibra Nagast or the Glory of Kings and Anqatsa Haimanot or the Gate of Faith.

Another Ethiopian historian who challenged the external paradigm is Teshale Tibebu. Teshale (1992) poignantly summarizes the argument as follows: “That Ethiopians are Semitic, and not Negroid; civilized, and not barbaric; are all images of orientalist semiticism in Western Social Science. Ethiopia is considered as the southwestern end of the Semitic world in Africa. The Ethiopian is explained in superlative terms because the ‘Negro’ is considered sub-human. That the heavy cloud of racism had been deeply embedded in the triplicate4 intellectual division among Social Sciences, orientalism, and anthropology – corresponding to Whites, ‘orientals’ (who included, Semitic people, who in turn included Ethiopians), and Negro and native American ‘savages,’ respectively – is common knowledge nowadays. … Ethiopians have always been treated as superior to the Negro but inferior to the White in Ethiopianist Studies because of the racist nature of the classification of the intellectual disciplines. It is quite revealing to see that more is written on Ethiopia in the Journal of Semitic Studies than in the Journal of African History.”

Perhaps the most persistent critique of the external paradigm was the great Ethiopian Ge’ez scholar, Aleqa Asras Yenesaw. Aleqa Asras categorically rejected the external paradigm as follows:

The notion that a Semitic fringe from South Arabia brought the writing system to Ethiopia is a myth.

1. South Arabia as a source of Ethiopian civilization is a political invention;

2. South Arabia was Ethiopian emperors inscribed a part of Ethiopia and the inscriptions in South Arabia.

3. There is no such thing as Sabaen script; it was a political invention designed to undermine Ethiopia’s place in world history.

Paleontological Evidence Places the Origin in Africa

Of course, Ethiopia in terms of place and time emerged much earlier than the name itself. The formation of a geographical feature called the Rift Valley predates in millions of years the word Ethiopia. It was in the Rift Valley of northeast Africa, thanks to the openings and cracks, that paleontologists have been able to unearth the earliest human-like species. At least 5 million years of human evolution has taken place before the naming of Ethiopia. Dinqnesh, Italdu, Garhi, ramidus or afarensis are names assigned within the last thirty years, even if they predate Ethiopia by a much longer time periods.

Ethiopia’s beginning, in paleontological terms, was in what we now know as southern Ethiopia. The Afar region is primal, for it is the cradle of human beings. The people of this region may have experimented with the oldest stone technology to develop our initial knowledge about plants and animals. They may have also experimented with languages and cultures so as to create groups and communities. They may have also been the first to map varying residential sites by moving from one locality to another.

In other words, the history of human beings begins in Africa, more specifically in the Rift Valley regions of northeast and southern Africa. As a result, African history is central to the early development of human beings. As the oldest continent on earth, it has been particularly valuable in the study of life. To many, Africa has made one of the most important, if not the most important contributions: the emergence of the earliest human ancestors about five million years ago. Evidence has shown that all present humans originated in Africa before migrating to other parts of the world. Paleontology is providing an incredible array of information on human origin. Furthermore, gene mapping and blood test are useful methods in the understanding of human beginnings in Africa.

Figure 4: Paleontological Site at Melka Kunture, central Ethiopia (Photo by

Ayele Bekerie)

Ethiopia has become one of the most important sites in the world in the unearthing and understanding of our earliest ancestors. Among the earliest human-like species found in Ethiopia are: Aridepithecus ramidus (4.4 – 4.5 myo), Australopithecus afarensis also known as Dinqnesh (3.18 myo), and Australopithecus garhi (2.5 – 2.9 myo). A. ramidus (an Afar word for root) is one of the earliest hominid species found in Aramis, Afar region by a team including Tim White and Berhane Asfaw. A. afarensis is widely considered to be the basal stalk from which other hominids evolved. Dinqnesh was found in Hadar, Afar region by Donald Johanson and his team in 1974. In addition, the oldest stone tools or the earliest stone technology, which is dated 2.5 million years old, was found in the Afar region by an Ethiopian paleontologist, Seleshi Semaw and his team in 1998.

Furthermore, Ethiopia has also provided us with a concrete fossil evidence for the emergence of modern human species, Homo sapiens, about 160, 000 years ago, again from the Afar region of Ethiopia. The fossil evidence supports the DNA evidence that traced our common ancestor to a 200,000-year-old African woman.23 “Geneticists traced her identity by analyzing DNA passed exclusively from mother to daughter in the mitochondria, energy-producing organelles in the cell.”24 Likewise, scientists from Stanford University and the University of Arizona have conducted a study to find the genetic trail leading to the earliest African man or Adam. According to this Y chromosome study, the earliest male ancestors of the modern human species include some Ethiopians, whose descendants populated the entire world.

According to Berhane Asfaw, an Ethiopian paleontologist, Edaltu, the probable immediate ancestor of anatomically modern humans and the 160,000-year-old fossilized hominid crania from Herto, Middle awash, Ethiopia, “fill the gap and provide crucial evidence on the location, timing and contextual circumstances of the emergence of Homo sapiens in Africa.”

In other words, as Lapiso Dilebo puts it, “Ethiopia is the primordial home of primal human beings and that ancient Ethiopian civilization ipso facto and by recent archaeological findings precedes chronologically and causally all civilizations of the ancients, especially that of Egyptian and Greco-Roman civilizations.”

I am also devoting more space to the paleontological aspect of Ethiopian history to show the way toward a paradigm shift in the reading of the Ethiopian past. It is very clear that humanity has gone through a set of dynamic evolutionary processes in Africa. What we now know as Ethiopia is central to part of an evolutionary transformation, which is attested by the presence of more than 87 linguistic groups that eventually emerged in it.

I think it will be fascinating to look into the historical convergence and divergence of all these linguistic/cultural groups, of course, from inside out.

Towards the People-Centered History of Ethiopia

A people-centered Ethiopian history will have at least the following foundations of material cultures. I would like to identify them as pastoral, inset and teff civilizations. Distinct communities and ways of lives have been established and perpetuated on the bases of these three civilizations in three major ecological zones. Moreover, we observe the emergence of national traditions and identity through the interactions of these civilizations.

Pastoral civilizations tend to concentrate in the lowlands or dry or semi dry lands of Ethiopia. The civilization is also conducive to coexist with the traditions and practices of both inset and teff civilizations. The inset civilization covers a wide region in the south and southwest, in an area known as woina dega or an ecological zone between the lowland and the highlands of Ethiopia. It is a tradition that is deeply rooted among the peoples of Wolaita, Gurage Betoch, Keffa and numerous other nationalities of the south. Teff civilization is the civilization encompassing central and northern Ethiopia that is the mountainous region of Ethiopia. It is important to note that I use the term civilization to denote the social, economic and cultural institutions that are established and sustained by the people. Pastoral, inset and teff are primary occupations of the people, but the essence of their lives is not entirely dominated by them.

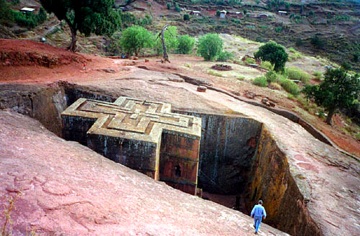

Figure 5: Bete Giorgis Church at Lalibela, northern Ethiopia

(Photo by Ayele Bekerie)

What are the main characteristics of these civilizations? The civilizations are home grown and deeply rooted. In other words, the people have succeeded in mastering ways of life that can be passed on from generations to generations. Furthermore, the civilizations are allowed to flourish in a pluralistic environment. In other words, they are civilizations that embrace or tolerate multilingual and multi-religious expressions. In all the three cases, we witness the presence of monotheistic or indigenous religious traditions, multiple linguistic expressions and patterns of social structures and functions under the umbrellas of these civilizations.

It is my contention that such inward approach may help us to fully understand, for instance the Gada age-grade system of the Oromos. The Gada system is regarded as one of the most egalitarian democratic system invented by the Oromos. The system allows the entire community to fully participate in its own affairs. All age groups have roles to play, events to chronicle and responsibilities to assume. I just can’t imagine how we can achieve modernity, or for that matter post-modernity in governance and development, without seriously considering such a relevant practice.

The inset civilization tends to allow its male members to venture to other professions far from home. A case in point would be the Gurages and the Dorzes. The Gurages are active in trading and business through out the country. The Dorzes are the weavers and cloth makers from homegrown resources for the larger population. Inset does not take a lot of space. A well-fertilized acreage at the back of the residential home may have enough inset plants, which are capable of meeting the carbohydrate needs of the entire household throughout the year.

Teff is part of the plow culture of the highlands. Just like inset, teff culture is unique to Ethiopia. No traces of teff or inset cultures are found in South Arabia. It is indeed in these significant material cultures that we begin collecting data in order to construct the long and diverse history of Ethiopia.

—–

Slideshow: Photos used in this article

——

Publisher’s Note: We hope this article will spark a healthy discussion on the subject. The piece is well-referenced and those who seek the references should contact Professor Ayele Bekerie directly at: ab67@cornell.edu.

About the Author:

Ayele Bekerie is an Assistant Professor at the Africana Studies and Research Center of Cornell University. He is the author of the award-winning book “Ethiopic, An African Writing System: Its History and Principles” Bekerie is also the creator of the African Writing System web site and a contributing author in the highly acclaimed book, “ONE HOUSE: The Battle of Adwa 1896-100 Years.” Bekerie’s most recent published work includes “The Idea of Ethiopia: Ancient Roots, Modern African Diaspora Thoughts,” in Power and Nationalism in Modern Africa, published by Carolina Academic Press in 2008 and “The Ancient African Past and Africana Studies” in the Journal of Black Studies in 2007.

Dear Professor Ayele,

I have always enjoyed your informative and sometimes thought provoking articles. I especially like this one because it shines light on the often ignored but rather more inclusive aspect of Ethiopian history. In my opinion, it is possible to find a middle ground between the two paradigms. Both share mostly the same facts, and as you have correctly pointed out, it is a matter of interpretation and most importantly, it is a matter of doing more research.

Is it true that the non-Africanization of Ethiopia in European literature started in earnest after the victory at Adwa in 1896? Do you agree?

Thank you much!

How does habesha history tie into the history of ancient Ethiopia that has been passed down to us by authors such as Homer and Herodotus who describe people who appear to have a Sudanese origin, phenotype and location?

I think part two of this article is great because the facts that are shown can be used to properly tell history of ethiopia. Some (earlier) European scholars, not all, have done humanity a serious injustice by teaching (false and misleading information) about ethiopian history and African history in general. You have some people in the u.s. that think that Ethiopians are not Africans. Its so sad. Thats why my major is African Studies to curb some of the western ignorance about Africa and her people.

Professor Ayele Bekerie,

You are a true scholar and educator. I have followed your regular history column on TADIAS Magazine for sometime now, I thought I would write you this note to say your work is appreciated! Thank you for sharing!

Dear Dr.Ayelé

What you are touching upon is, I think, the tip of the Iceberg! That would be the Day when the Full Edifice, Down to the Core, is bared and stands in Full Glory of Day Light. I am looking forward to the day; at least, my grandchildren will have Ethiopian History 101 for what it is and ought to have been.

Here is few suggestion for whatever it is worth:

1. In an Afterword for his groundbreaking book Orientalism the late Edward W Said writes:

“What makes all these fluid and extraordinarily rich actualities difficult to accept is that most people resist the underlying notion: that human identity is not only not natural and stable, but constructed, and occasionally invented t outright. Part of the resistance and hostility generated by books like Orientalism. Or after it, The Invention of Tradition and Black Athena is that they seem to undermine the naïve belief in the certain positivity and unchanging historicity of culture, a self, a national identity”

I am sure and hope you read this and his other books. If by any chance not, you will enjoy and be able to benefit from the specificity and the Big Picture he paints in a very detached and astute way. I recommend him to one and all.

2. Avery erudite Afari Ethiopian friend of mine, Yusuf Yasin, has recently presented a paper in San Jose, California on the murky relation ship between the former allies TPLF and TPLF and its aftermath. Among the important points he raises though was what Said refers to as occasional invited .That, or some aspect of it, is exactly taking place right now in Eritrea. Since this paper is on line on EMF you may take look at it and defiantly benefit from it, I believe

.

3. I think it must have been June 1974 when I walked into the office of the late Poet Laureate Thegaye GM. to say Hello! and exchanging on the latest Talk of the Town and the Nation. So much was going and there was no time to sift and digest. As usual, with out much ado he picked up a book and started reading a poem. At the end he signed the book and gave it to me. The poem was Maneh? (Who are You?) and the book was his collection of his poems Esat wey Abeba. It was the first piece on the collection. It is a lamentation for lost self, lost identity. The Blues, if you will, in African American sense. That seqoqaw was the Ethiopian version of Trail of Tears here in the USA. It is painted in multi color with words. Since then I have forever been reading it and what is more have read for hundreds of people in my prolonged detention years. I am sure you have read it. Taking one more look will enhance you undertaking. What is more, you will be able to see others have also tried to tackle the very same area in a different format.

4. One last thing . The other day I was watching Aljezzera (AJE) and watched a forum where how this conflicted issue of individual identity, nationality and religion is being handled in Lebanon. Incidentally Yusuf too mention Lebanon in connection with Eritrea.

I very much admire and appreciate what you do. It an endeavor that needs a great sensitivity and sensibility. It seems you have them. and look forward that it comes out in a book format

With Regards

Óiechá Óní_Óné

Let us not deny that the northern ethiopian history is tied in to south arabian history. As to who influenced who, I think it was a two way street. Just because it is fashionable to be afrocentric these days does not mean that nothern ethiopian axumite history is somehow “African”? What does African mean anyway really? Like it or not, Axumite history is not related to Kenyan or Conglese history. The horn of Africa is a distinctly different part of Africa whose civilization and language is related to Middle East Sudan and Egypt, maybe even India.

What is your take on this article then?

http://www.spiegel.de/international/world/0,1518,473358,00.html

I am not Historian; however, we need to be careful not to pass the boundaries.

I cannot believe what Mary wrote “just because it is fashionable to be afrocentric these days does not mean that nothern ethiopian axumite history is somehow “African”?” So geography is not reason enough to describe Axum as African. I believe it is almost a source of physical pain for people like Mary to admit that African civilzations were actually ummmm…. how shall I put it?–African?

Just examine the Logic “What does African mean anyway really? Like it or not, Axumite history is not related to Kenyan or Conglese history. The horn of Africa is a distinctly different part of Africa whose civilization and language is related to Middle East Sudan and Egypt, maybe even India.”The diversity within Africa–between Kenyan culture or Ethiopian Culture is being used to Deafricanise Axum. This is like saying that Italian culture is distinct from Northern European culture, so Italy should not be thought of as European.

And its one thing to talk about links betweeen North East Africa and the Middle East culture–after all the semitic languages spoken in the Middle East developed in Ethiopia.But India? What are the links between Indian culture and North East African culture, besides ancient trade? So we can describe Axum as Vaguely Indian but not African, despite the fact of its geography? The wonders of self delusion!

I agree with Mary and I think she has some interesting/valid points. Our history is different from other African countries, thought this was an interesting article.

Ladies, (Mary & Azeb),

You are missing the whole point! What the good professor is saying is – that the horn of Africa is the starting point of history for all humankind!! It is Ethiopian influence you would find in South Arabia and not the other way around. The so called ‘Sabean’ inscriptions you find on stelea in South Arabia should actually be named Axumite and not Sabean!

If the connection you are trying to establish with South Arabia is based on the assumption that it all started in the Horns, then we have no problem. Civilizations evolved in so many places,i.e., Ancient Egypt in the north (which by the way is an African civilization), Axum in the Horn – which by the way is preceded by another civilization Da’amat, Zimbabwe in Southern Africa, Songhai in West Africa etc. Here, I’m talking only about Africa. Then there are the Asian civilizations of Babylon/Mesopotamia, Persia, India China etc. All these precede European civilizations of Rome & Greece. The two way street came after that because of trade, wars etc. Nobody denies that. But terms like ‘..What does Africa means anyway really?’ ‘..fashionable to be afrocentric’??? to say the least divulge blatant complacency!

Pleeease don’t miss the point Prof. Ayele is trying to make. We are fed up of history written from the point of view of Europeans. We should thank historians like Ayele for trying to dig out what really happened thousands of years back!

By the way, Prof. Ayele, the Ge’ez alphabet if more related to the hieroglyphics of Egypt to some people (including me). What’s your take on that.

Please read the second paragraph 6th line as, ‘Some of these precede….’ instead of, ‘All of these….’

Last paragraph, please replace as follows:

‘By the way, Prof. Ayele, the Ge’ez alphabet is more related to the Egyptian hieroglyphics according to some historians & alphabet experts. What’s your take on that?’

I found the article highly informative, the comments very engaging. I would be very much interested in learning how the past of ethiopia shaping todays ethiopia..what does the Future for ethiopia. can Professor Ayele address this in future article.

Very happy with the article and the comments that followed the article,like Saba I want to read more,if I am not mistaken people like the late Steven Biko liked our history as Ethiopians,like thier dream can Ethiopia rise again?.I saw in a sort documentary,some body left a bible by the grave side of Stev Biko and in the bible was written the following words in gold,rise and shine,I hope proffesor Ayele you do not find ny comment emotional,Iam only a student.Also my excuses to Saba,a proffetional like you not me can answer her question,thank you very much and God bless you.

very fascinating stuff.

Sorry again I have lived so long here in Holland that I make many spelling mistakes, in my comment above,brave,thanks.T.Gebregzi