Why Ethiopians are nostalgic for a murderous Marxist regime

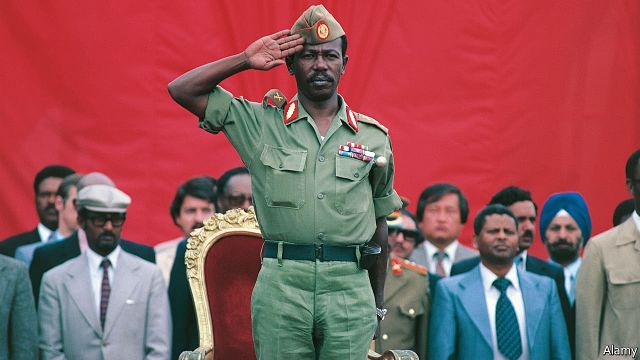

IN AMBO, a town in central Ethiopia, a teenage boy pulls a tatty photo from his wallet. “I love him,” he says of the soldier glaring menacingly at the camera. “And I love socialism,” he adds. In the picture is a young Mengistu Haile Mariam, the dictator whose Marxist regime, the Derg, oversaw the “Red Terror” of the 1970s and the famine-inducing collapse of Ethiopia’s economy in the 1980s. Mr Mengistu was toppled by rebels in 1991 before fleeing to Zimbabwe, where he still lives. He was later sentenced to death, in absentia, for genocide.

But the octogenarian war criminal seems to be growing in popularity back home, especially in towns and among those too young to remember the misery of his rule. When Meles Zenawi, then prime minister, died in 2012, a social-media campaign called for Mr Mengistu to return. In the protests that have swept through towns like Ambo since 2014, chants of “Come, come Mengistu!” have been heard among the demonstrators.

Asked by Afrobarometer, a pollster, how democratic their country is, Ethiopians give it 7.4 out of 10. They give the Derg regime a 1. Yet even some of those old enough to remember life under Marxism are giving in to nostalgia, admits a middle-aged professor at Addis Ababa University. The coalition that ousted the Derg, the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), introduced a system of ethnically based federalism in 1995 that critics say favours the Tigrayan minority. After bouts of ethnic violence, most alarmingly this year, many now look back fondly on Mr Mengistu’s pan-Ethiopian nationalism.

“The general perception is that whatever the Derg did was out of love for the country,” explains Befekadu Hailu, a human-rights activist, who is himself no fan. Mr Mengistu fought a victorious war against Somalia in the 1970s, and waged a homicidal campaign against secessionists in Eritrea, then a region of Ethiopia, for more than a decade. The EPRDF, in contrast, oversaw the loss of Eritrea and with it access to the sea when it allowed an independence referendum in 1993.

The Derg’s policies were ruinous: nationalising almost every firm; forcing peasants at gunpoint onto collective farms, where they starved. Mr Mengistu was also more brutal than any Ethiopian ruler before or after. But the EPRDF is struggling to win the hearts of ordinary Ethiopians. Its heavy-handed propaganda—which includes ideological “training” for students and civil servants, and an annual celebration of its victory over the Derg—are widely met with contempt.

“When you have no hope for the future you go back and try to find some light in the past,” says Hassen Hussein, an activist who now lives abroad. The country’s most popular musician is Teddy Afro, a 41-year-old whose songs celebrate Ethiopia’s former emperors and its feudal past. The ruling party has yet to come up with such a catchy tune.