Tadias Magazine

By Tadias Staff

November 7th, 2019

New York (TADIAS) — “What is good for women is good for the community,” Ethiopian social entrepreneur and community activist Dr. Bogaletch Gebre had declared in a profile interview with Tadias Magazine published sixteen years ago this Fall highlighting her non-profit organization, KMG (The Kembatti Mentti Gezzima). “What I discovered in our work,” she told us, “is not changing the whole society at once, but to change one person at a time. And it works.”

Dr. Bogaletch passed away this week at the age of 59 here in the U.S.

“The former scientist and marathon runner’s quiet revolution saved tens of thousands of girls from potential injury or death in Ethiopia, which has the second highest number of women living with FGM globally, data from anti-FGM charity 28TooMany shows,” Reuters points out, adding that “Bogaletch was determined to stop female cutting in Ethiopia after it killed her sister and nearly claimed her own life.”

In 2013 after being awarded the King Baudouin Prize in Belgium for confronting “culturally entrenched taboo subjects,” Dr. Bogaletch explained her simple message to the community elders in Ethiopia who defend the harmful tradition: “Daddy, you lived your time. This is our period, our children’s period. We don’t want to kill our children. I hope you are wise enough to accept that.”

BBC noted: “She helped reduce cases of FGM from 100% of newborn girls to less than 3% in parts of Ethiopia,” and described FGM in Africa and the Middle East as being “seen as a traditional rite of passage and is used culturally to ensure virginity and to make a woman marriageable. It typically involves removing the clitoris, and can lead to bleeding, infections and childbirth problems.”

Dr. Bogaletch ran marathon races in Los Angeles, California to raise funds for her projects in Ethiopia, which included efforts to create awareness on a wide ranging issues — in addition to FGM — that are detrimental to women’s health, livelihood, education and environment informed by her upbringing in rural Ethiopia. The literal translation of her non-profit, The Kembatti Mentti Gezzima, means “Women of Kembatta pooling their efforts to work together.”

Per the Tadias profile:

Daughter of a farmer, Bogaletch was taught how to read and write by a relative; she would study by the campfire at night after completing her daily house chores and responsibilities. In a village where the education of girls was rarely encouraged, Bogaletch’s father was reluctant to allow his daughter to continue with her primary school education. Occasionally, she was given permission and she would willingly make the six-mile run to and from school. “I would never dream of complaining,” she says, “I felt fortunate; one of the chosen few.” “Demands at home kept me away from school for weeks, sometimes months,” she continues, “but still I skipped grades, completing four levels in three years.” She became the first girl in her village to be educated beyond the fourth grade. By the time she was nine she was reading and translating court documents for her father, a task he had previously paid others to do for him. She helped people in her community write their court applications free of charge. “As a sign of respect in Kambatta tradition, a father is called after his first-born son, and a mother after her first-born daughter,” she explains, “Imagine his surprise when my father’s peers started calling him Father of Bogaletch.” With her father now won over by her diligence and perseverance Bogaletch was allowed to attend the one and only women’s boarding school in Addis Ababa on a government scholarship. She then went on to attend Hebrew University in Jerusalem on a full scholarship. Saving her stipend money with great effort she demonstrated her appreciation to her father by building him a new house with a corrugated tin roof‚ the only one of its kind in Zato. “People came from miles to see what a woman could do. Now I wanted to do more,” she confessed. Once people in her village saw what women could achieve with education they were willing to let their daughters become educated too and a ripple-effect ensued. Bogaletch continued her education securing a Fulbright scholarship to the University of Massachusetts and later completing a PhD program in Epidemiology at UCLA. Returning to Ethiopia after 13 years she realized the disparities in education opportunities in her hometown and began to conceive of a way to give back to her community.

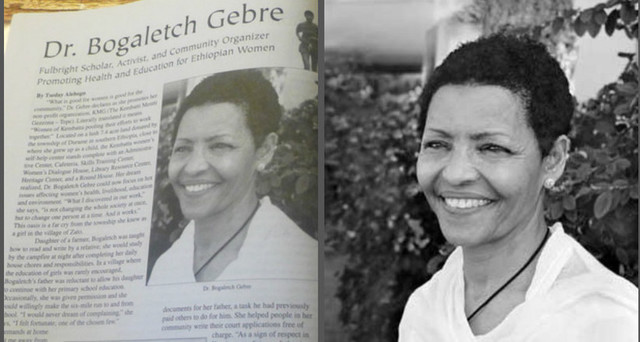

Dr. Bogaletch Gebre. (From Tadias Magazine print issue 2003)

Speaking about the legacy of Dr. Bogaletch, the Africa director of the advocacy group Equality Now, Faiza Mohamed, told Reuters: “It was most impressive how she empowered the youth to reject the practice; it is a wave of hope and change into the community. It’s critical to involve the youth, have a dynamic partnership and engage with them.”

—

Related:

‘Wave of hope’ to end FGM in Ethiopia as activist pioneer dies (Reuters)

Bogaletch Gebre: Talking Female Circumcision Out of Existence (NYT)

Women’s Rights Activists Bogaletch Gebre wins King Baudouin Prize (BBC News)

Fulbright Scholar & Community Activist Uplifting Women (TADIAS)