Tadias Magazine

By Tadias Staff

Published: Monday, September 21st, 2015

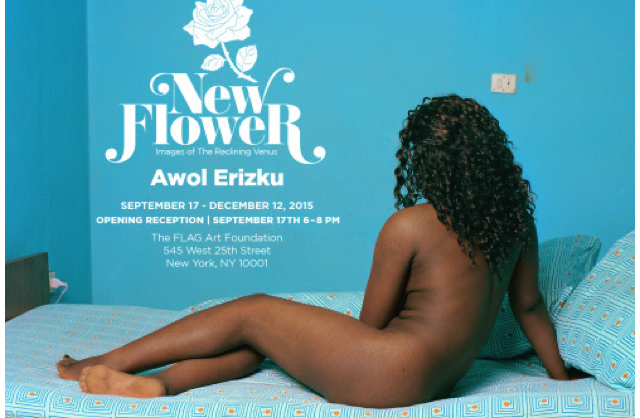

New York (TADIAS) — Conceptual artist Awol Erizku’s New Flower: Images of the Reclining Venus exhibit, currently on display at The Flag Art Foundation in New York City’s Chelsea Gallery District, is his latest body of work challenging mainstream narratives and representations of beauty.

A few weeks prior to the opening of New Flower Erizku had posted Manet’s Olympia portrait on his Instagram account and shared “I’ve always had an issue with this painting.” Olympia had created controversy in its time primarily because the reclining nude in the portrait was a prostitute. The problem Erizku points to, however, is what Manet’s audience ignores — the side presence of the black servant bringing in flowers for the model. Where is the black beauty that is front and center in a work of art? That’s the central question that Erizku focuses on as he pays commercial sex workers in Addis Ababa to strike the same pose.

Climbing up the stairs to the 10th floor exhibition space one is greeted at the entrance with large-framed portraits of Ethiopian women, unconventionally nude, lying on beds that seem to take up the entire space of claustrophobia-inducing, minimally furnished hotel rooms.

Turning the corner and heading into the gallery’s main space pink neon lights burn on a wall emblazoning the words Addis Ababa in Amharic font — it’s the literal translation of the exhibit title, New Flower, which is also the name of Ethiopia’s capital city where Erizku traveled to and made these portraits in 2013. A mixtape co-produced with DJ SOSUPERSAM played during the reception highlights Ethiopian Canadian music sensation The Weeknd (Abel Tesfaye) as well as songstress Aster Aweke. Across from the neon sign a table features copies of the exhibit press release and an elaborate flower arrangement — fresh flowers among the flowering beauty of Ethiopian reclining nudes.

Born in Ethiopia and raised in the Bronx Erizku seeks an alternate interpretation of the spaces that black bodies are allowed to inhabit in portraits. While his 2012 show at Hasted Kraeutler Gallery challenged Vermeer’s portrait, Girl with a Pearl Earring, with a photographic reinterpretation of an Ethiopian woman entitled Girl with a Bamboo Earring, his current exhibit focuses on introducing a more universal image of the reclining venus.

(New Flower. Photo: Flag Art Foundation)

Erizku’s reclining venus is a black beauty. In one portrait entitled Elsa an empty chair replaces the space where Manet’s black servant once stood bearing flowers; it’s an invitation for a visitor to enter the space, or perhaps to join and jumpstart a conversation on what is considered beautiful. The environment for this conversation is narrow, just like the windowless rooms that the nudes inhabit, but Erizku is pushing for this space to grow. Out of the thirteen images in the exhibit there is only one photograph of a room with its windows flung wide open, finally revealing a glimpse of the city’s scenery; the model in this portrait also appears more relaxed. It feels like a flicker of the artist’s hope for the acceptance and wider inclusion of universal blackness in modern art.

No matter how elegant a reclining pose the young Ethiopian models may hold, however, none of them are smiling. Their eyes are hauntingly sad; the girl in the portrait entitled Aziza looks downright bewildered. This is not an effort to make commercial sex work appear glamorous or a campaign for women’s sexual liberation; it’s impossible to brush away the harsh realities of their lives. According to the U.S State Department’s Trafficking in Persons report from last year cited in the exhibit’s press release “the central market in Addis Ababa is home to the largest collection of brothels in Africa, with girls as young as 8-years-old in prostitution in these establishments.” This is the untalked-of cost of rapid progress and globalization in Ethiopia’s capital city. And yet, to an Ethiopian audience, it is striking that the names of Erizku’s models (pseudonym or otherwise) are anything but gloomy: Desta (happiness), Tigist (patience), Zewditu (the crown), Worknesh (you are golden), Bruktawit (blessed), Aziza (cherished), Feker (love), and Meskerem (the month of September when Ethiopians celebrate the new year). Here again is beauty hidden in plain sight, the inherent royalty and humanity of the black model. The black servant does not exist in Erizku’s reconceptualization of the reclining venus and the girls’ names further nudge the windows open.

Erizku is not the first Ethiopian-born artist to photograph commercial sex workers in Ethiopia. In a 2011 interview with Tadias Magazine, award-winning photographer and artist Michael Tsegaye described how he spent close to two weeks “talking, eating meals together, drinking tea and coffee” with commercial sex workers in the Sebategna area of Merkato (known unofficially as the red light district) and spending time in the rooms where they live before photographing them. He noted that most of the commercial sex workers came to Addis Ababa from different towns across the country, lured as much by better financial prospects as the desire to remain anonymous in their line of work.

While Tsegaye spoke directly to commercial sex workers and took monochrome photographs of them in their natural setting, Erizku hired a translator to help him communicate with the girls — who themselves were selected by his assistant — as they agreed to recline in the nude in hotel rooms chosen by the artist. The walls of the rooms are painted in solid bright red, sunshine yellow, lime green or pastel baby blue colors and otherwise unadorned except for the jarring presence, in four of the portraits, of either a poster of a white Jesus or a westernized image of the Virgin Mary. Christianity was introduced in Ethiopia long before its advent in Europe and the walls and ceilings of ancient Ethiopian churches traditionally depict the Virgin Mary and her Son as well as angels more commonly with brown faces. In Erizku’s portraits one of the white Jesus posters contains a verse in Amharic stating: “For him who believes in me there is eternal life.” The masculine tone and non-black representation is out of place and in stark contrast to the models’ personal belongings including handmade wooden crosses in traditional Ethiopian design worn around their necks on black string. As much as this exhibit is about the status of blackness and interpretations of beauty in the art world, it is also about breaking cultural taboos and shattering globalized western narratives.

The day after the opening reception Erizku Instagrammed “I like making art that evokes an emotional response from people, I hope I was able to show you all something new & different.” Not only does Erizku share new images of the reclining venus but he is taking both the art and media establishments to task, shaking and stirring up a much-needed conversation about moving black bodies from the sides and bringing them to the foreground in modern art portraiture. Can we do this without slipping into simplified narratives that label the artist primarily as a “black artist” when he/she attempts such interpretations? That is the second challenge.

Erizku stirs in us the possibility to reconceptualize the space for black beauty in the new global art history being made. His work is soaringly hopeful and gut-wrenching in its honesty at one and the same time.

New Flower (Addis Ababa): Images of the Reclining Venus is on exhibit in New York City until December 12th, 2015.

—

If You Go:

The FLAG Art Foundation Presents

Awol Erizku: New Flower | Images of the Reclining Venus

from September 17 – December 12, 2015

545 West 25th Street, 10th Floor

New York, NY 10001

Tel (212) 206-0220

www.flagartfoundation.org